Dispatch

Clause

At its essence a clause is a pattern like pattern = body that checks a term or sub-term against some pattern, and then if it matches transforms it to the body.

Patterns

There are many terms and many types of patterns to match those terms. At the end of the day all they do is bind variables to substitute into the body, and fail or succeed, but they are Turing-complete with the use of guards and view patterns. There are some interesting pattern languages, like Stratego/XT and a Haskell pattern-matching DSL. Sketch of pattern-matching without handling binding:

match : Term -> Pattern -> Bool

# wildcard, matches any value without binding a name

match term _ = True

# matches the atom a

match term ^a = term[i] == a

# matches the symbol tree with atom f

match term ^f a b c = term[0] == f && term.length >= 4

# matches any symbol tree besides a single atom

match term (f@_) a = term.length >= 2

# literal match

match term [(1, "x"), {c: 'a'}] -> term[i] == [(1, "x"), {c: 'a'}]

# matches any list starting with 1 and ending with 2

match term [1, ..., 2] = term[i][0] == 1 && term[i][-1] == 2

# matches a and the rest of the record

match term {a: 1, ...} = term[a] == 1

# matches both patterns simultaneously

match term pat1 AND pat2 = match term pat1 and match term pat2

# matches either pattern

match term pat1 OR pat2 = match term pat1 or match term pat2

# desugars to f u_ ... = let pat = u_ in ..., where u_ is a unique name

match term ~pat = True

# type tag

match term (a : b) = a elemOf b

# guard, arbitrary function

match term (a | f a )= f a

# view pattern

match term (f -> a) = match (f term[i]) a

We need special patterns for positional arguments, keyword arguments, variadic functions, and so on.

Positional arguments

foo w x y z = z - x / y * w

foo 1 4 2 0

# 0-4/2*1

Positional arguments are what you get in most languages, the list of parameters at the call site is bound to the list of variable names at the definition site.

Positional arguments support currying, for example:

c x y = x-y

b = c 3

b 4

# 1

Positional arguments may be filled by the special syntax _ to write a partial application:

sub x y = x - y

sub1 = sub _ 1

# equivalent definition

sub1 x = sub x 1

sub1 3

# 2

All the underscores of a call are regrouped to form the parameters of a unique function in the same order as the corresponding underscores.

Per [KKSV95], an uncurried function symbol has an arity n and a function application f(t1, ... , tn) is formed from f and n terms t1,…,tn. In a curried system there are no arities and function applications are formed starting from a nullary constant f and applying the binary “application” operator, like App(...App(App(f,t1),...),tn) but more concisely written as left-associative juxtaposition f t1 ... tn. We ignore the partially-applied system mentioned by Kennaway here and just assume the use of term matching.

Partial application creates a function that takes one or more omitted parameters and plugs them into f to produce a final result. Currying allows easy partial function application for lastmost positional parameters and keyword parameters, which in turn allows using higher-order functions more easily, e.g. passing a partially-applied function as the argument to map. For example map (add 2) [1,2] = [3,4]. Without currying this would have to use a lambda to perform the partial application like map (\x. add 2 x). So in Stroscot positional parameters and keyword parameters are curried. This allows passing any function “directly”, without “wrapping” it in an anonymous function.

The parentheses for a curried function don’t matter, e.g. all of the following are equivalent:

((f 1) 2) 3

(f 1 2) 3

f 1 2 3

Currying is independent of function call syntax, e.g. with C-style syntax we would write:

f(1)(2)(3)

f(1,2)(3)

f(1,2,3)

for the various currying possibilities.

R allows some kind of “partial matching” so you can write f(x, , y) instead of \a -> f(x, a, y). Seems stupid.

The parameters can either be bound positionally, meaning the syntactic position at the call site determines what formal parameter an argument is bound to, or with a keyword associating the argument with the formal parameter. Keywords allows reordering parameters. Also keyword parameters can have a default value (optional parameter).

The arity of a function is how many positional parameters it has. A function with arity 0 is nullary, arity 1 is unary, arity 2 is binary, arity 3 is ternary, and in general arity n is n-ary. Functions with no fixed arity are called variadic functions.

Functions are usually named with a function symbol identifying the function. There are also anonymous (nameless) lambda functions, which have somewhat restricted syntax compared to named functions.

Functions that have functions as parameters or results are called higher-order functions. Functions that don’t are called first-order functions.

Keyword arguments

Keyword arguments let you give names to each argument at the call site. Then these are matched to the definition site:

foo w x y z = z - x / y * w

v = foo (y:2) (x:4) (w:1) (z:0)

# 0-4/2*1

v == foo {x:4,y:2,w:1,z:0}

# true

Keyword arguments allow passing arguments without regards to the order in the function definition, making the code more robust to forgetting argument order. You can mix positional and keyword arguments freely; positions are assigned to whatever is not a keyword argument.

v == foo {z:0} {w:1} 4 2

# true

Julia separates positional arguments from keyword arguments using a semicolon (;). These create a second form of argument, keyword-only arguments. These must be specified using the keyword syntax.

kw a b ; c = a+b+c

kw 1 2 {c=2}

Regarding currying, of course keyword-only arguments do not work with currying. But if they are mixed keyword-positional arguments then specifying most of them using keywords and leaving the rest as curried positional parameters can work:

kw a b c = a + b + c

zipWith (kw {b=1}) [1,2] [0,1]

--> [2,4]

You can also specify a subset of the arguments to generate a partially applied function:

a = foo (y:2) (w:1)

b = a (x:4) (z:0)

b == v

# true

Using the variable name in braces by itself uses the value of that variable in scope:

y = 2

x = 4

w = 1

z = 0

v == foo {w,x,y,z}

# true

Default arguments

Default or optional arguments are basically keyword arguments, but rather than erroring if the property is not set they just use the default value.

a {k:1} = k + 1

a # 2

Rob Pike says Go deliberately does not support default arguments. Supposedly, adding default arguments to a function results in interactions among arguments that are difficult to understand. But Pike admits that it is really easy to patch API design flaws by adding a default argument. Expanding on this, it seems default arguments have a good place in the lifecycle of an API parameter:

A new parameter can be added to a function, just give it a default value such that the function behavior is unchanged.

The whole argument can be deprecated and removed on a major release, hard-coding the default value

The default value can be deprecated and then removed on a major release, forcing the value to be specified.

An existing parameter can be given a default value without breaking compatibility

One side effect of this lifecycle is it gravitates towards default parameters, because those don’t break compatibility. So programs accumulate many default parameters that should be made into required parameters or removed. This is probably why developers say default parameters are a code smell (nonwithstanding the internet’s main opinion, which comes from C#’s implementation breaking ABI compatibility in a way that can be fixed by using regular overloading). But regular pruning should be possible, just do occasional surveys as to remove/make mandatory/leave alone. And, without default parameters, adding or removing a parameter immediately breaks the API without a deprecation window, so it is effectively impossible - you have to make a new method name. This is why Linux has the syscalls dup, dup2 and dup3. IMO having deprecated parameters is better than trying to come up with a new name or having version numbers in names.

A wartremover issue provides 4 potentially problematic cases for default arguments. Going through them:

Automatically allocated resource arg - this is deallocated by the finalizer system in Stroscot, hence no resource management problem. To avoid statefulness, the pattern is to default to a special value like

AutoAllocateand do the allocation in the method body.Config - a big win convenience-wise for default arguments, only specify the parameters you care about.

Delegated parameter: this is nicely handled in Stroscot by implicit parameters. Hence a pattern like

ingest {compressor = None} = ...; doIngestion = { log; ingest }; executeIngest = { prepare; doIngestion }; parseAndExec cmdline = { compressor = parse cmdline; executeIngest }is possible. Once you realize the compressor is important you can remove the default and make it a keyword parameter - the default can still be provided as a definition in an importable module, and you get an unset argument error if no implicit parameter is set.Faux overloading like

foo(i, name = "s")- useful just like overloading.

The verdict here is that defaulting is a power vs predictability tradeoff. The obvious choice given Stroscot’s principles is power. There are no easy solutions for adding new behavior to a function besides adding a default argument flag to modifying an API in a backwards-compatible way, so default arguments are necessary. And default arguments have been used in creative ways to make fluent interfaces, giving programmers the enjoyment of complex interface design. The added implementation complexity is small. Security concerns are on the level of misreading the API docs, which is possible in any case. Adding a warning that a default argument has not been specified, forcing supplying all parameters to every method, seems sufficient.

Modula-3 added keyword arguments and default arguments to Modula-2. But I think they also added a misfeature: positional arguments with default values. In particular this interacts very poorly with currying. If foo is a function with two positional arguments, the second of them having a default value, then foo a b is ambiguous as to whether the second argument is overridden. When do we decide to put in the default value?

We can resolve this by requiring parentheses: (foo a) b passes b to the result of f a {_2=default}, while foo a b is overriding the second argument. But it’s somewhat fragile. Stroscot’s answer is that defaults must be syntactically supplied if they are overridden.

opt (a = 0) (b = 0) = a + b

opt 1 2 = 3

(opt 1) 2 = (1+0) 2

A lambda or builder works for anything tricky.

ReasonML uses an empty tuple to mark the end of supplied arguments.

Implicit arguments

12D. Functions, procedures, types, and encapsulations may have generic parameters. Generic parameters shall be instantiated during translation and shall be interpreted in the context of the instantiation. An actual generic parameter may be any defined identifier (including those for variables, functions, procedures, processes, and types) or the value of any expression.

These behave similarly to arguments in languages with dynamical scoping. Positional arguments can be passed implicitly, but only if the function is used without applying any positional arguments. If the LHS contains positional arguments only that number of positional arguments are consumed and they are not passed implicitly.

foo w x y z = z - x / y * w

bar = foo + 2

baz a = bar {x:4,y:2} - a

bar 1 2 3 4

# (4 - 2/ 3 * 1) + 2

((0-4/2*1)+2)-5 == baz 5 {z:0,w:1}

# true

baz 1 2 3 4 5

# Error: too many arguments to baz, expected [a]

Similarly keyword arguments inhibit passing down that keyword implicitly:

a k = 1

b k = k + a

b {k:2}

# Error: no definition for k given to a

A proper definition for b would either omit k or pass it explicitly to a:

a k = 1

b = k + a

b' k = k + a k

b {k:2} == b' {k:2}

# true

Implicit arguments use keyword syntax as well, so they override default arguments:

a {k:1} = k

b = a

c = b {k:2}

c # 2

For functions with no positional arguments, positions are assigned implicitly left-to-right:

a = x / y + y

a 4 1

# 5

Atoms that are in lexical scope are not assigned positions, hence (/) and (+) are not implicit positional arguments for a in the example above. But they are implicit keyword arguments:

a = x / y + y

assert

a {(+):(-)} 4 1

== 4/1-1

== 3

The module scoping mechanism protects against accidental name conflicts in large projects.

Infix operators can accept implicit arguments just like prefix functions:

infix (**)

x ** y {z} = x+y/z

Output arguments

7F. There shall be three classes of formal data parameters: (a) input parameters, which act as constants that are initialized to the value of corresponding actual parameters at the time of call, (b) input-output parameters, which enable access and assignment to the corresponding actual parameters, either throughout execution or only upon call and prior to any exit, and (c) output parameters, whose values are transferred to the corresponding actual parameter only at the time of normal exit. In the latter two cases the corresponding actual parameter shall be determined at time of call and must be a variable or an assignable component of a composite type.

7I. Aliasing shall not be permitted between output parameters nor between an input-output parameter and a nonlocal variable. Unintended aliasing shall not be permitted between input-output parameters. A restriction limiting actual input-output parameters to variables that are nowhere referenced as nonlocals within a function or routine, is not prohibited.

b = out {a:3}; 2

b + a

# 5

Output arguments can chain into implicit arguments, so you get something like the state monad:

inc {x} = out {x:x+1}

x = 1

inc

x # 2

It might be worth having a special keyword inout for this.

inc {inout x} =

x = x+1

Variadic arguments

Positional variadic arguments:

c = sum $arguments

c 1 2 3

# 6

c {$arguments=[1,2]}

# 3

Only syntactically adjacent arguments are passed, e.g.

(c 1 2) 3

# error: 3 3 is not reducible

a = c 1

b = a 2

# error: 1 2 is not reducible

There are also variadic keyword arguments:

s = print $kwargs

s {a:1,b:2}

# {a:1,b:2}

A variadic function has no fixed arity. So can currying and variadic functions coexist? Well consider a variadic function sum:

sum == 0

# true

sum + 1

# 1

g = sum 1 2 3

g == 6

# true

g 4 5

# 15

So even though g == 6, g is different from 6 - g is both a function and non-function at the same time. Similarly sum is both 0 and a function. This causes confusion. In particular the issue is there are multiple interpretations of a function call: it could be a partial application waiting for more arguments, or it could be a complete application with the intention to use defaults for default parameters and terminate the varargs list. To avoid this confusion we need to know when the function call is complete. It seems to be a common misconception (e.g. in the Flix principles) that this means currying and variadic functions cannot be in the same language. But there are several approaches:

nondeterminism: Just accept that the meaning of

g`depends on its usage. This is not a good option because it means things that look like values aren’t actually values.a special terminator value, function, or type. For example in ReasonML every function needs at least one positional parameter. There are no nullary functions; a definition or function call without any positional parameters is transformed to take or pass an empty tuple argument (). ReasonML accumulates parameters until it first encounters a positional parameter, then defaults all default parameters and (if it supported varargs) ends varargs, creating a partially-applied function taking only positional parameters. So

add {x=0,y=0} () => x + ycan be called asadd {x=3} {y=3} () = 6oradd {x=3} () = 3, including splitting the intermediate values likeplus3 = add {x=3}; result = plus3 (). Another example is Haskell printf which can dofinalize (printf "%d" 23)(In Haskell the finalize is implicit as a type constraint). Essentially we construct typesT = end | (param -> T); finalize : end -> .... It is also possible to use a specificendvalue, likesum end = 0,sum 1 2 3 end = 6.using a explicit length parameter. SO proposes passing the length as the first parameter, like

sum 4 1 2 3 4 = 10, but this is error-prone and inferior to just passing a listsum [1,2,3,4].using the syntactic boundary: Arguably both of the previous are hacks. They do allow currying, but at the expense of exposing the dispatch machinery. Generally currying is not needed and the function is fully applied at its use site. Per [MJ06] Figure 6, around 80% of calls are fully applied with known arguments. Finalizing varargs at the site of the function call is a simple and clear strategy:

sum 1 2 3 = 1 + 2 + 3 (sum 1 2) 3 = (1+2) 3

This is the same behavior as languages without currying (

sum(1,2,3)vssum(1,2)(3)) and is only really complicated if you think too much about consistency. If we want more arguments we can use a lambda, or a builder DSL likefinalize (f `add` a `add` b).

Concatenative arguments

Results not assigned to a variable are pushed to a stack:

1

2

3

%stack

# 1 2 3

% is the most recent result, with %2 %3 etc. referring to

less recent results. These stack arguments are used for positional arguments when not

supplied.

{a = 1}

extend % {b=2}

extend % {c=3}

shuffle

# {b=2,a=1,c=3}

Priorities

Priority is novel AFAIK but powerful, and generalizes the CLOS dispatch system. I thought about making all clauses the same priority by default, but concluded that specificity was likely going to be confusing hence is better off opt-in. Specificity is found in predicate dispatch and Zarf’s rule based programming, but both are far off from practical languages.

CLOS method dispatch

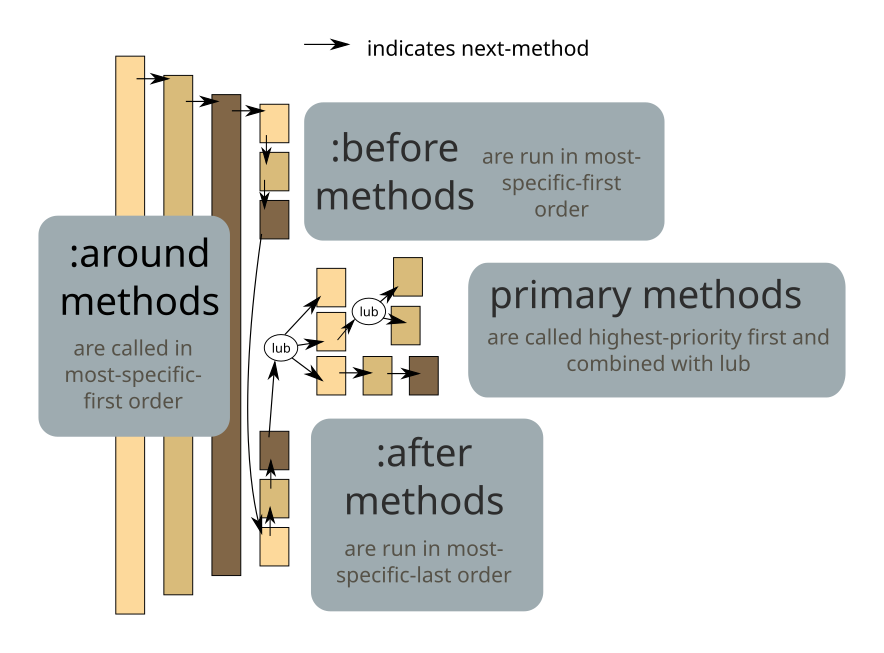

CLOS has method qualifiers before, after, and around. The basic idea of method combination can be seen here:

But it turns out these can simply be implemented with priorities around_clause > before_clause > after_clause > prioHigh and next-method. before and after:

before f = around { f; next-method }

after f = around { next-method; f }

Guards are handled by calling next-method on failure:

(around f | c = d) = if c then d else next-method

Overloading

Overloading is having methods with the same name but different type signatures. A special case is operator overloading. Even the Go FAQ, an opponent of overloading, admits that overloading is useful and convenient. Per [IHR+79] there are several reasons:

The careful use of overloading can be a valuable asset for readability since it offers an additional degree of freedom for the choice of suggestive identifiers that convey the properties of the entities they denote.

It is natural to use the same name for an output operation such as print` over many different types, or a numeric operation such as + over floats and ints. (ad-hoc polymorphism)

[edited] The writers of a package can certainly not foresee all possible uses. In particular they may not (and should not) be aware of the fact that their package is used with overloaded operations at a different type than the authors envisioned. Nonetheless extending a package to a novel user-defined type is in general quite valuable. The developer should be able to use suggestive names so as to reuse code with no changes necessary. Overloading achieves this reuse.

To these I would add that overloading solves the expression problem: if all functions are open, then naturally it is easy to add both new operations and novel instances of operations at new types.

Although in many cases using separate function names can lead to a clearer API, supporting overloading does not prevent this. And there are cases where overloading is the right choice. Suppose you are trying to wrap a Java library that makes heavy use of overloading. Name mangling using simple rules will give relatively long names like divide_int_int. More complicated rules will give shorter name like div_ii, but the names will be hard to remember. Either way, overloading means no mangling is needed in the API at all, a strictly better alternative. Similarly the Go API is full of families of functions like FindAll : [Byte] -> [[Byte]], FindAllString : String -> [String] which differ only by their type. These additional name parts cannot be guessed easily and require looking up the API docs to determine the appropriate version. Overloading means only the base name needs to be remembered.

Per the FAQ, Go supposedly “does not support overloading” and restricts itself to matching only by name. Actually, overloading is still possible in Go by defining a function which takes variadic arguments of the empty interface type and manually dispatches with if statements and runtime type analysis. What’s missing in Go is that the compiler does not implement an overloaded dispatch mechanism. The FAQ claims that implicit dispatch will lead to confusion about which function is being called. In particular Ian Lance Taylor brings up the situation where an overloaded function application could be resolved to multiple valid clauses. Any rule that assigns an implicit priority of clauses in going to be fragile in practice. More generally this is referred to as incoherence in Rust and Carbon - how do you pick the instance?

Stroscot’s solution is to require the system to produce a unique normal form. So it is an error if the multiple valid clauses produce different results, and otherwise the interpreter will pick an applicable clause at random. When compiling, the most efficient implementation will be chosen. If you want to work around this, you can use qualified imports or priorities and specify the precise implementation you want, avoiding the incoherence.

This solution has several properties, compared to Carbon:

It requires code to behave consistently and predictably.

It pushes the conflict to the last possible moment - observable behavior at runtime. There is no possibility of it being the compiler’s error, e.g. a situation like the orphan rule’s limitations. Now in practice equivalence checking is hard, but just the mindset is an improvement.

Disambiguation mechanisms are required to fix the error, but both qualified imports and priorities can be specified in code you control, at the application level.

The Hashtable Problem

Per Carbon, the “Hashtable problem” is that the specific hash function used to compute the hash of keys in a hashtable must be the same when adding an entry, when looking it up, and other operations like resizing. So a hashtable type is dependent on both the key type and hashing function implementation. The hash function cannot change across method invocations - it must be coherent.

For example:

class HashSet(Key:! Hashable) { ... }

fn Hash[self: SongLib.Song]() -> u64 { ... } // version 1

fn Hash[self: SongLib.Song]() -> u64 { ... } // version 2

fn SomethingWeirdHappens() {

var unchained_melody: SongLib.Song = ...;

var song_set: auto = HashSet(SongLib.Song).Create();

song_set.Add(unchained_melody);

assert (song_set->Contains(unchained_melody))

}

If the Hash function is incoherent, then this assertion can fail. But we also want to allow multiple versions of Hash, to solve the diamond dependency problem and other such issues. It is inherent in any solution that involves both scoped implementations (i.e., not global) and open extension (i.e., methods can be defined in separate pieces).

The simplest solution is to include the hash function in the creation of the table, like HashSet(SongLib.Song, Hash_v1).Create(). Then every use of the hash table uses this function and it is coherent. The issue is, do we pay for an extra pointer in the hash table? Likely not, as it is a constant and the compiler can propagate it through the program so it does not need to be explicitly stored. When we are dynamically using hash tables of unknown types and hash functions, then maybe there is a problem, but none of the other solutions optimize this case either, and JITs are amazingly intelligent.

This is also why I hate types: on the one hand we want to specify that the hash function is fixed, so it is part of the type, but on the other hand it is painful to write out the hash function as part of the type every time. With model checking it doesn’t matter; the hash function is stored as part of the value and we can mention it in a refinement type or not as needed.

Now, there are other potential ideas. Like global implementation names - wouldn’t it be great if everyone everywhere used the same method names for the same things? It sort of works with IP addresses. But if we go up one level to domain names there is a ton of typosquatting and snatching after a domain expires. Same with package names and leftpad. There is really no way to stop two unrelated people from independently using the same name for different methods. Scoped names just work a lot better. The downside is we have to load up the debugger or whatever in order to see which hash function is actually used. It’s a hash function though - when was the last time you messed with the default hash functions?

Context sensitivity

Per Carbon, one effect of the way overloading is resolved by this dispatch method is that the interpretation of source code changes based on imports. In particular, imagine there is a function name, and several different implementations are defined in several different libraries. A call to that function will behave differently depending on which of those libraries are imported:

If nothing is imported, it is an undefined method error.

If only one is imported, you get the specific version that is imported.

If multiple are imported, the methods will be run in parallel, and most likely give an ambiguity error unless they are identical

Actually this sort of problem is why Python recommends to always use scoped imports, somepackage.foo instead of just foo. But it is very convenient to write bare method names when you are writing a DSL and the like, and the “hiding” import works just as well.

Also, this dispatch applies to implicit parameters. So when a function takes an implicit parameter, e.g. a hash parameter as the hash function for a hash set, then it is not the hash clauses in scope at the point of definition that are used. Rather, it is the hash clauses in scope at the call site. And if you add an explicit keyword assignment of the hash function somewhere up above, like foo { hash = hash }, then if foo calls HashSet.create it will be the hash clauses in scope at that keyword assignment that are used, so there is no issue with the call being outside your code like mentioned here. But the imported clause will be scoped anyway so most likely it doesn’t need to be overridden - if it worked for the library author it should work for you (and have identical semantics).

This context sensitivity does make moving code between files more difficult. Generally, you must copy all the imports of the file, as well as the code, and fix any ambiguity errors. Actually, that happens already in other languages. But it’s really terrible if there are implicit keywords in use - then you will to figure it out in debugging. But the IDE can probably assist here.

Steelman 1C says “[The language] shall require explicit specification of programmer decisions and shall provide defaults only for instances where the default is stated in the language definition, is always meaningful, reflects the most frequent usage in programs, and may be explicitly overridden.” The decisions part seems suspect - programmers make lots of decisions, like what to eat for lunch, and these should not all be specified. For the defaults, the method of choosing a specific overload is stated in the language definition. It will always be a user-written definition, so it is of course meaningful. “Most frequent usage” is sort of a cop out as not all usages are common yet programmers nonetheless expect them to work. But it is certainly the case with the nondeterminism solution described later that only correct usages will work, and thus those will be the most frequent.

The explicit overrides part does make sense, and so there is a syntax for referring to clauses within a specific file and even a specific clause within a file.

There is also Steelman 2D “Multiple occurrences of a language defined symbol appearing in the same context shall not have essentially different meanings.” This we get around by making all overloaded symbols library-defined.

Return type overloading

In Haskell, typeclasses can cause ambiguity errors. For example show (read "1") gives “Ambiguous type variable ‘a0’ arising from ‘show’ and ‘read’ prevents the constraint ‘(Show a0, Read a0)’ from being solved.”

Following [OWW95] the ambiguity can be further attributed to read. The function show :: Show a => a -> String takes a value of type a, so dynamic dispatch can deduce the type a and there is no ambiguity. In contrast read "1" produces a type out of nowhere and could be of type Integer or Double. Since read has a constraint Read a and does not take a value of type a as argument it is said to be return type overloaded (RTOed).

A brief categorization of some RTO functions in GHC’s base libraries:

Conversion functions, functions that extract a value:

toEnum :: Enum a => Int -> a,fromInteger :: Num a => Integer -> a,fromRational :: Fractional a => Rational -> a,encodeFloat :: RealFloat a => Integer -> Int -> a,indexByteArray# :: Prim a => ByteArray# -> Int# -> aOverloaded constants:

maxBound :: Bounded a => a,mempty :: Monoid a => a,def :: Default a => aMonadically-overloaded operations:

pure :: Applicative f => a -> f a,getLine :: Interactive m => m String,fail :: MonadFail m => String -> m a,ask :: MonadReader r m => m rparsec :: (Parsec a, CabalParsing m) => m aType-indexed constant:

get :: Binary t => Get t,readsPrec :: (Read a) => Int -> ReadS a,buildInfo :: HasBuildInfo a => Lens' a BuildInfo,garbitrary :: GArbitrary f => Gen (f ())GADT faffing:

iodataMode :: KnownIODataMode mode => IODataMode mode,hGetIODataContents :: KnownIODataMode mode => System.IO.Handle -> IO modeCreating arrays of type:

newArray :: (MArray a e m , Ix i) => (i,i) -> e -> m (a i e),basicUnsafeNew :: PrimMonad m, MVector v a => Int -> m (v (PrimState m) a)Representable functors:

tabulate :: Representable f => (Rep f -> a) -> f a,unmodel :: TestData a => Model a -> a, whereRepandModelare type synonym families of their respective classes

There are several ways to resolve an RTOed expression.

Defaulting

Defaulting is considered by Haskell Prime Proposal 4 to be a wart of the language. clinton84 want a switch NoDefaulting to remove it entirely. But GHC plans to move in the opposite direction, expanding its use by allowing more and more classes to be defaulted, and recently allowing defaulting rules to be exported. ref

In Haskell 98 defaulting is limited to numeric types, where it allows numerical calculations such as 1 ^ 2 - ^ is generic in the 2 so must be defaulted. This usage can be replaced with using a single arbitrary-precision type for all literals that can accurately hold both Integer and Double, and then Julia’s conversion/promotion mechanism in operations.

With -XOverloadedStrings every string literal is wrapped in a call to fromString : IsString s => String -> s. The usage is that Haskell has several text types, such as ByteString and Text, and also some people define newtypes over them. The defaulting to IsString String seems to mainly be added for compatibility with existing source code. Probably Julia’s conversion/promotion mechanism is sufficient for this as well. The corresponding IsList class for -XOverloadedLists has no defaulting rules, and nobody is complaining.

ExtendedDefaultRules for the Show, Eq, Ord, Foldable and Traversable classes is simply a hack for Curry-style type system oddities in GHCi - since the involved classes have no RTOed functions, it is unnecessary in an untyped setting. For instance, show [] is unambiguous in a dynamically typed language - it matches a rule show [] = .... In Haskell it has a polymorphic type forall a. [a] and no principal Show instance because GHC does not allow polymorphic type class instances. GHCi defaulting to [Void] instead of [()] would make this clear, but Void was only recently added to the base library so GHCi uses ().

GHC also supports defaulting plugins, supposedly to specify default device types and numeric types for tensors in haskell-torch. The defaulting can likely be solved by using default or implicit parameters. And Haskell-torch is a port of PyTorch so everything can be solved by using dynamic types. AFAICT there are no working defaulting plugins currently available.

Signatures

The most direct way to resolve RTO in Haskell is to specify the type. There is an inline signature read x :: Float, defining a helper readFloat :: String -> Float; readFloat = read, or using type application read @Float. Rust traits are similar, the turbofish specifies the type explicitly, like iterator.collect::<Vec<i32>>, and the type inference for defaulting is local rather than global. Ada similarly can disambiguate by return type because the type of the LHS is specified.

Inline signatures and type application can be replaced in a dynamic language by passing the type explicitly as a parameter, read Double or read Float, using normal overloading. Sometimes it can be shortened by making the type itself the function, Vec i32 iterator or Vec iterator instead of collect (Vec i32) iterator. Either way, the resulting syntax is uniform, and more standard and simple than the observed Haskell / Rust syntax.

Multiple parameters can be handled in the obvious way, foo A B, or we can pack them in a term foo (term A B).

Return types signatures

Julia essentially uses the same syntax I’m planning, zeros(Float64,0), with strict matching on the type Float64. Contrariwise Martin Holters, a professor in Germany researching audio processing (i.e. not a language designer), filed a Julia issue to introduce more complex syntax foo(x,y,z)::Type that specifies the return type. The issue generated no substantial discussion for 5 years so could be ignored, but let’s go through it.

Martin says a dedicated syntax would be clearer than the “return type as first argument” convention because the type passed is used inconsistently. He gives a list of function calls using Float64:

map(Float64, 1) = 1.0: this appliesFloat64to 1. IMO this should error because1 : Intis not a collection type.map(Float64, (1, 2)) = (1.0,2.0): good, so long as the overloading of types as conversions is remembered. It would be clearer to writemap (convert Float64) (1, 2) = (1.0,2.0)rand(Float64) = 0.16908130360440443:Float64is the return type, good.rand(Float64, 1) = Vector{Float64} [0.1455494388391413]: returning a vector is a bit inconsistent with the previous. It would be better to have a separate functionrandvecthat takes a varargs list of dimensions, sorandvec(Float64)would return a 0-dimensional array. With this using interpreting the parameter as the element type is fine.zeros(Float64) = Array{Float64, 0} [0.0]: This always returns an array and interprets as the element type, like the proposedrandvec. Good.zeros(Float64, 1) = Vector{Float64} [0.0]; Writing the full return type likezeros(1)::Vector{Float64}is verbose, and you would inconsistently writezeros(1,1)::Matrix{Float64}orzeros(1,1)::Array{Float64, 2}for a 2D array, compared tofillwhich has no types involved in calling it and is length invariant.

So the inconsistencies he points out are due to standard library oddities, rather than the syntax, and in the practical cases of zeros / randvec Martin’s syntax would be worse IMO.

Martin also says foo()::T should invoke the method foo()::S such that S is the largest type with S<:T. It’s not clear why - he just says it “seems logical” but admits it doesn’t “translate into any real benefits”. Practically, one has to write the return type out, and writing the exact type used in the dispatch clause is simpler than picking out a supertype. For a trivial example, writing default {None} instead of default {None,1,2} makes it clearer that None will be used as the default. Furthermore it avoids conflicts like for default (Int|{None}) if there were two rules default Int = 0; default {None} = None

Inference

The case where a parameter approach falls down is when we desire an inferred type rather than specifying the type directly on the function. For example (fromInteger 1 + fromInteger 2) :: Int, Haskell pushes the constraint down and deduces fromInteger 1 :: Int. If we went with giving the type as a parameter we would have to write fromInteger Int 1 + fromInteger Int 2, duplicating the type. With a function expression of fixed type let f = id :: Int -> Int in show (f $ read "1") or case statement show (case read "1" of (1 :: Int) -> "x") the type is far removed from the ambiguous read.

It is arguable whether inference is desirable. The programmer has to perform the same type inference in their head to follow the path the compiler is taken, which can make code tricky to understand. The meaning of an expression is context-dependent. But the original typeclasses paper [WB89] mentions resolving overloaded constants based on the context as a feature. So this section discusses possible ways of implementing the context resolution.

One approach is similar to this C++ thing. We create a “blob” type that represents an RTO value of unknown type as a function from type to value. Then we overload operations on the blob to return blobs, delaying resolution until the full type can be inferred. Furthermore the blob can store its type in a mutable reference and use unsafePerformIO to ensure that it resolves to the same type if it is used multiple times. Or it can be safe and evaluate at multiple types. This requires overloading every function to support the blob, so can be some boilerplate.

A little simpler approach is to use a term, so e.g. read "x" is a normal form. Then you overload functions to deal with these terms. This works well for nullary symbols like maxBound - you implement conversion convert maxBound Float = float Infinity and promotion will take care of the rest. The issue is that an expression like read "1" + read "2" will not resolve the return type, and returning read "3" is inefficient. I think the best solution is to return a blob. So this ends up being the blob solution but with readable literals for the first level of return value.

Another approach is to add type inference, but as a macro transformation. All it has to do is infer the types using Hindley Milner or similar and insert explicit type parameters for the RTOed functions. But this is really the opposite of what Stroscot aims for. Stroscot avoided static typing to begin with because there are no principal types if you have union types. For example a value of type A may take on the type (A|B) or (A|C) depending on context. The inserted types would have to be principal, negating the advantage of dynamic typing. Furthermore you’d have to use more macros to specify type instances and types of functions.

Despite the naysayers I still like my original idea of using nondeterminism: an overloaded function f : Something a => a is interpreted as (f A) amb (f B) amb ..., combining all the typeclass instances. Disambiguating types using annotations is then replaced with disambiguating the result using assertion failures. This actually preserves the semantics of the static typeclass resolution AFAICT. In the discussion on Reddit, it was brought up that if there are a lot of overloadings or the overloadings are recursive, it would be slow, exponential in the number of function calls. That’s for a quite naive implementation; I think the compiler could do a type analysis and give good performance for most cases. HM also has exponential blowup on pathological cases. Overall I think this approach is the best, but it is not clear if it is actually helpful because features like automatic promotion will make many programs ambiguous.

Implicit conversions

Steelman 3B: “There shall be no implicit conversions between types.”

Implicit conversions per Carbon are defined as “When an expression appears in a context in which an expression of a specific type is expected, the expression is implicitly converted to that type if possible.” So for example you have foo : i64 -> String and i : u32 and you can write foo i and it is equivalent to foo (convert_u32_to_i64 i). (Assume here that i64 and u32 are disjoint)

There are some issues with implementing this in Stroscot. First is that Stroscot has “sets” rather than “types”. Second is that Stroscot has no expectations, only runtime exceptions. So revising this definition it is something like “When an expression appears in a context which throws an exception on certain values, the expression is implicitly converted to not be one of those exception-causing values.” So for example we have foo (i : i64) = ... and i = u32 1. foo i evaluates to an no-matching-clause exception, so again the expression is implicitly converted by inserting foo (convert i). Notice we have lost some information - we do not know that foo expects an i64 or the type of i. In convert, we have the actual value of i, which is for our purposes probably better than its type. But to produce a u64 it is the return-type-overloading problem above, and we will have to follow the same solution patterns of a blob value or nondeterministically producing all implicit conversions. If there are multiple valid implicit conversions though, then it gets very complex to prove they are equivalent (and maybe they aren’t - like a print command, it will of course print the full value and give different results for different values).

Julia has a clever “promotion” multimethod dispatch pattern, discussed on the “Compiler Library” page. This avoids the RTO problem because the conversion is done inside foo and it knows what types it can handle. So first the rule tries to match the type exactly, then if no clauses match, there is a fallback clause where it can try converting to its preferred type, next most preferred type, etc. This honestly seems better than implicit conversion, you can easily trace the code and there is no need to change the dispatch machinery. It is just a little more verbose, one fallback clause for each function vs. a global fallback. But I would say this is worth it, as the desired conversion is often function-specific. (example needed)

Implementation

The full dispatch mechanism is as follows:

dispatch clauses args = do

warnIfAnyPrioEqual clauses

starting_clauses = find_no_predecessors clauses

callParallel starting_clauses

where

callParallel clauses = lubAll (map call clauses)

call clause = clause args { next-method = callParallel (find_covering methods clause) }

lubAll = fold lub DispatchError

This depends on the lub primitive defined in Conal’s post. lub evaluates both sides to HNF, in a timeboxed fashion. If both sides are exceptions then an exception is returned. If one side gives an exception but the other doesn’t, then the other side is returned. If both sides evaluate to HNF and the heads are equal, the result is the head followed by the lub of the sub-arguments. Otherwise the context is used, f (a `lub` b) = f a `lub` f b. lub is an oracle, analyzing the whole program - we want return type overloading, and that return values not accepted by the surrounding context are discarded. This falls out naturally from doing the analysis on the CPS-transformed version of the program, or expressing lub as amb in the term-rewriting formalism with some post-filtering on bottoms (a amb b rewrites to both a and b non-deterministically).

The dispatch semantics is that all methods are run in parallel using lub.

The way Stroscot optimizes dispatch is:

eliminate all the statically impossible cases (cases that fail)

use profiling data to identify the hot paths

build a hot-biased dispatch tree

use conditionals for small numbers of branches, tables for large/uniform branches (like switch statements)

The standard vtable implementation of Java/C++ arises naturally as a table dispatch on a method name. It looks like ‘load klass pointer from object; load method from klass-vtable (fixed offset from klass pointer); load execution address from method (allows you to swap execution strategies, like interp-vs-C1-vs-C2, or multiple copies of C2 jit’d depending on context); jump’. But usually we can do better by building a custom table and fast-pathing the hot cases.

Cliff says what we do for overloaded calls doesn’t matter so long as in practice, >90% of calls are statically resolved to one clause. As Steelman 1D puts it, we must “avoid execution costs for available generality where it is not needed”.

THe inline-cache hack observes that, while in theory many different things might get called here, in practice there’s one highly dominant choice. Same for big switches: you huffman-encode by execution frequency.

TODO: check out pattern dispatch paper

Karnaugh map with profiling data